East Asian Servanthood in Western Church Leadership

Serving faithfully amid a culture of self-promotion in churches

I’m an extrovert, but people often mistakenly presume I’m an introvert because I’m a good listener and don’t shoot my mouth off. In contrast with the extroverted tendency to ‘speak before you think’ – which growing up I naïvely ascribed to the West as a whole – many East Asians including myself were reared to ‘think before you speak’ (or in some cases not speak at all) so we didn’t offend or disrupt the status quo.1

So when I first moved to the UK, I was surprised that I didn’t face much culture shock. On the contrary, I felt like I’d unwittingly found cultural equilibrium. I experienced the UK to be in the middle of introverted Japan and extroverted America, with a slight lean towards the former: people were very socially conscious (e.g. reading the atmosphere, beating around the bush, queueing), but were also able to voice one’s opinions freely and confidently if necessary. I found that to be a really good balance.2

I’ve now been in the UK for more than a decade, during which I’ve been given leadership opportunities in western churches. This has allowed/forced me to be assertive and speak up more.

Not that I didn’t have any opinions before; rather, I’d always felt expressing one’s opinions was in essence expressing one’s superiority – that my opinions were of value and thus worth listening to – and therefore hubristic. Neither does it mean I wasn’t confident enough to voice them: my American upbringing has imbued me with a self-confidence (antithetical to British self-deprecation), and my experience as an officer in the Singapore army has taught me how to lead and speak with authority.

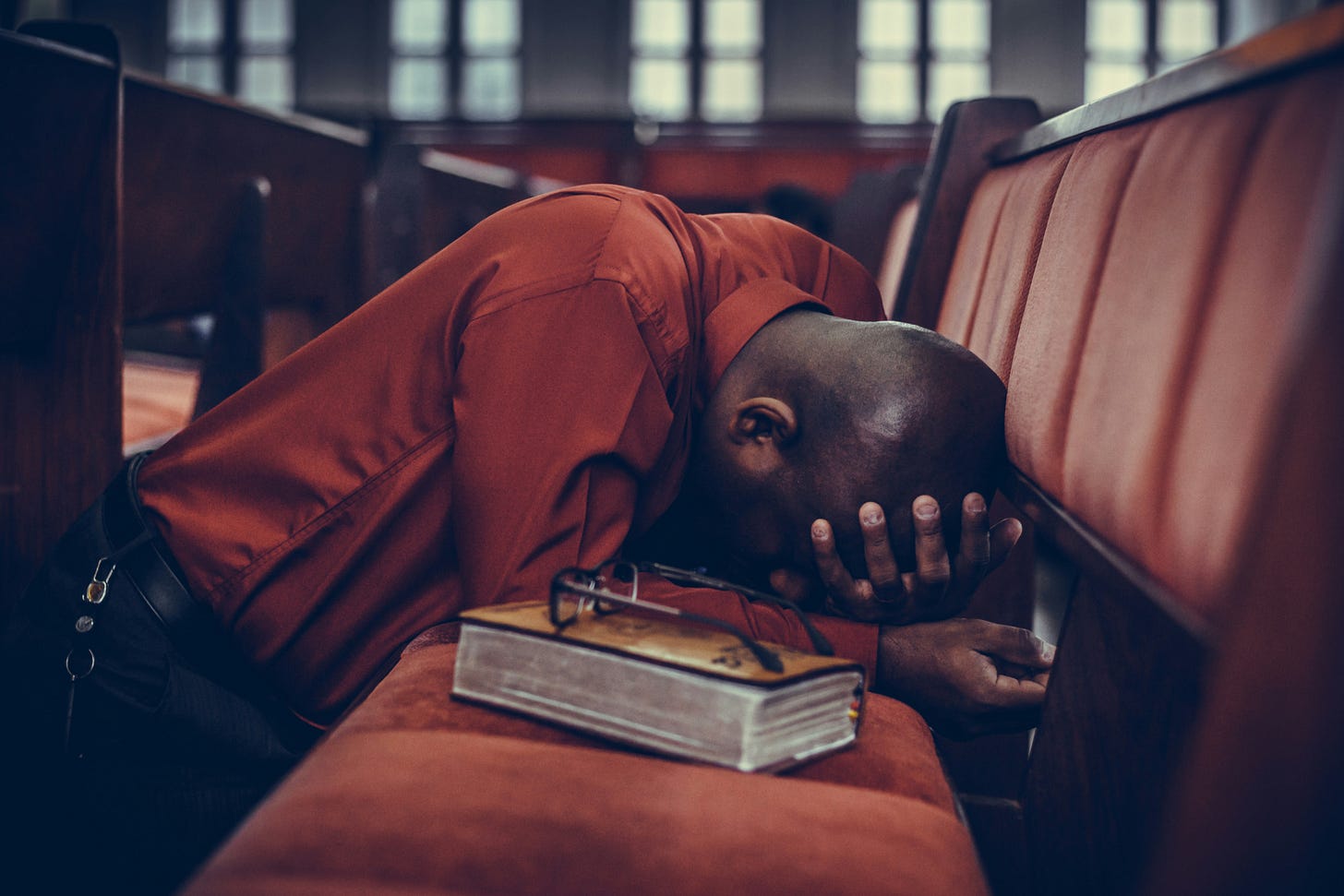

I now appreciate being heard. I’ve come to value bringing what I have to say to the table. And as an extrovert, I don’t mind being the centre of attention. Yet I seek to ensure this inclination is always subservient to the primary call of making God the centre of attention.3 (As John the Baptist says in John 3.30, ‘He must increase, but I must decrease.’) Over time I’ve realised this posture comes naturally because of an engrained foundational instinct to be silent and submissive out of respect for higher authority, as well as for others – in other words, to serve more than to lead.

I was delighted to recently discover the book Leadership or Servanthood? by Hwa Yung, bishop emeritus of the Methodist Church in Malaysia. He incisively critiques the overemphasis of developing leaders in churches – as well as a prevailing culture of hubris and selfish ambition – and then points to the Bible and Jesus to demonstrate that the primary focus of discipleship should be on the formation of servants. The danger is, ‘until and unless the principle of servanthood has been internalized in our lives, any talk about leadership development invariably encourages self-seeking ambition.’4

Although Hwa doesn’t explicitly connect his thesis with East Asian culture, I posit that there’s something in Confucian cultures that predisposes us to follow the servanthood call more easily. I’m thankful I’ve culturally inherited this principle of servanthood – this consideration of others before consideration of self – which serves as a necessary antidote.

I’ve seen many Christians, particularly in the West, seeking self-promotion.5 Blatant hankering for positional status and institutional authority. Unsubtle ingratiation with prominent leaders to gain a foothold on the ladder. This ‘holy’ dogfight has always rubbed me the wrong way, left a bad taste in my mouth. I remember being super uncomfortable when church friends would joke about me being a ‘big name’; I refrain even from bantering about fame or acclaim, because vocal repetition has the power to transform notions into ‘truth’.

Obviously I’ve met many who don’t participate in or condone this at all. I was chatting with a Swedish pastor who dislikes the title-chasing proclivities of younger leaders, whose attitude and behaviour noticeably changes – a sudden glint in their eye – the moment they find out he leads his church.6 And a British worship director taught me how to redirect compliments: when met with ‘Worship was great, you were amazing!’, respond with, ‘What a joy and privilege to be part of a singing congregation!’

I recognise that God has blessed me with gifts and skills, and in some cases even status and authority, but I always feel icky the moment attention is drawn to me. I seek to remain humble by (in the words of C. S. Lewis) not so much thinking less of myself (risk of false humility), but by thinking of myself less. But simultaneously, I do have a responsibility to steward every role, relationship and opportunity to the best of my abilities; and if I’m promoted as a result, great, but only because it means a wider sphere of influence for God’s Kingdom, and not for myself.

(Side note: It’s worth noting the real danger of East Asian submission to western leaders who are controlling, perhaps even abusive. My deeply-embedded ethic of respect for elders and authority figures has at times made it near impossible for me to see when I was actually mired in toxic situations. The indebtedness you feel towards those who’ve invested in your life can lead to an undying loyalty, which at worst can morph into a blind following at the expense of your own dignity and welfare. It required others to point out the wrongness of the situations I found myself in before I could recognise, acknowledge and give myself permission to step away.)

As I continue to serve in the western church, I find people affirming me for who I am and what I do, encouraging me to step fully into the authority Christ has given me – all of which I’m thankful for, and has been a healthy corrective to the extreme East Asian propensity for self-negation. But I never want to forget my humble roots, that to be a disciple of Christ is first and foremost to be a servant (diakonos), even a slave (doulos), as the apostles so identified themselves in their epistles.7 My friend once said: ‘We’re all willing to be a somebody for Jesus. Are you willing to be a nobody for Jesus?’

Hwa quotes from Thomas à Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ:

No man can live in the public eye without risk to his soul, unless he would prefer to remain obscure. No man can safely speak unless he who would gladly remain silent. No man can safely command, unless he who has learned to obey well.8

I was reared to be content with remaining in obscurity, and remaining in silence. In the army, before I commissioned as an officer, I first spent 11 months obeying well. Only now do I see how all of that has shaped me to be the leader I am today, how those grounded instincts guard me from this very risk to my soul.

I’m proud to have been raised in East Asia, with its cultural values of servanthood and humility. They are of the Kingdom, and I pray will continue to protect me from the temptation of selfish ambition and self-glorification, especially in leadership. May I forever be quick to listen and slow to speak; to pursue being, not a leader first, but a servant.

I end with a quote from Stephen Neill:

For the Christian there is one place and only one place – the lowest place. That is the command of the Lord, and it is binding upon us all. As you enter on the work of ministry you must seek the place of hardest work, greatest sacrifice and least recognition, and there you must be content . . . If when you are toiling contentedly in the lower place those who have the authority to call men to special spheres in the Lord’s vineyard come to you and say, ‘Friend, come up higher; this place of great eminence and heavier responsibility is the one in which you can now best serve,’ you may accept the call without fear and without anxiety; but never, never, never, if you have yourself desired or sought what is called advancement in the church.9

I’ve previously shared how this impacted me and other East Asians in our reluctance to volunteer ourselves to serve in western churches – how we needed to be ‘invited’ or ‘nominated’ by others – and how that can be perceived by westerners as apathy instead of respect:

Asian hierarchical culture means that silence and submission is generally viewed as respectful, whereas in western culture it can be perceived as apathy, lack of leadership skills or agreement/consensus (even if they disagree).6 Paul Tokunaga explains how ‘it feels presumptuous, aggressive and even arrogant to raise a hand and say, “I’ll do it.” ... What is called respect in one culture looks like apathy in another’.7 Van Opstal continues: ‘In some cultures leaders are applauded for stepping up; in others leaders disqualify themselves by assuming they can lead. They need a sponsor to invite them to lead.’8

I expound my experience of the UK in this YouTube interview (17:54~20:20).

‘It’s not that great leaders of the church have no ego or self-interest. Indeed they are incredibly ambitious – but their ambition is first and foremost for Christ and his Kingdom, not for themselves’ – Hwa Yung, Leadership or Servanthood?: Walking in the Steps of Jesus (Carlisle: Langham Global Library, 2021), p. 24.

Hwa, p. 23.

Obviously, Christians in East Asia aren’t immune to this. The hierarchical authority patterns in Confucian cultures can easily lead to the abuse of power or controlling pastoral leaders – see Hwa, pp. 35, 107.

I don’t really get starstruck, because witnessing leader after leader fall from grace – both personally and more widely – has disabused me of the notion that they’re exceptional. The best leaders are those who stay humble and servanthearted (e.g. warm, approachable, down to earth).

‘[I]n the New Testament epistles where the apostles identify themselves as “servants” of Christ, it is the humbler word doulos (slave or bondservant) that is used, rather than just diakonos (servant). […] Both are close to the bottom of the social ladder in the first-century world. These two words and their verbs are used about fifty times in the New Testament for service to God and the church’ – see Hwa, pp. 9, 11.

Hwa, p. 24.

Hwa, p. 63.

Well said. Love it!

Wow wow wow… So much to process… so much language for things I have not been able to formulate.

But revelation hit me in your little side note about noticing toxic relationships 😭 not so much seen this in western leadership I have been under but in friendships with ‘western’ Christians.

And also your footnote about respect influencing the way we volunteer and step up (or not). So helpful.

Thank you Justin! Can’t wait to read more 🙏🏼